Space applications for large terrestrial markets - how I think about space investing

Every once in a while I get to speak with generalist investors. The discussion always looks something like this:

Me: …so I invest in the space industry

Them: you mean asteroid mining? Nah that doesn’t sit well with me

Me: Not really. I mean the 40 thousand Starlink user terminals in Ukraine. I mean every phone being able to get a signal anywhere. I mean the 50% of climate change indicators measured only from space. I mean better positioning for autonomous mobility, medical data on human cells aging… that’s what I mean.

Them: uh, oh

Introduction

Over the last two years or so, I developed a set of ideas and narratives about investing in the space domain. I have also been pretty vocal about this “space applications for large terrestrial markets” concept, but never fully developed the narrative in writing. This article should serve as the definitive explanation of how I derived this approach, what I mean by it and why is it important.

Agenda

Here is what we have on the menu

The story - a foundation for the article

Introduction + agenda - what are we talking about

Problem statements - which problems plague the space industry

Why upstream/downstream doesn’t really make sense & what I prefer instead

Exits in the space industry

Some criteria for successful public exit and how to achieve them

The point of the whole article

Two differences making this a relevant narrative

A few more notes

A lot of counterarguments to my thesis

Problem statements to begin with

Before I dive into the topic, here are a couple of problem statements I have worked with when developing this approach

space companies run into financial difficulties - poor public market performance, tight cash lifelines, slow cash inflows, low revenues, high costs

space companies have product problems - amazingly often I have space entrepreneurs telling me how they built something only to find there is virtually no demand or a predictable issue hindering the product’s success

Those are connected to a gadget disease, a common illness among the space community where engineers devise a marginal improvement to their current problem and then convince themselves riches are imminent

too many startups “help facilitate the space economy” - till you notice this very economy consists of other such startups and doesn’t differ much from a house of cards

Truth be told, it is always easier to be a space company serving other space companies - problem identification is easier, you know all your customers on a first-name basis and meet them every year in the same bars in Paris, Colorado Springs, and DC. But well, big businesses tend not to be built the easy way.

Space also has a reputation problem. If you’d go interview strangers on the street, most would have close to no idea about the space industry beyond NASA and SpaceX. More thoughtful members of the sample would bring up the space debris armageddon, “sending billionaires to space” and the carbon footprint of rocket launch.

The “large terrestrial markets” approach, I hope, can help navigate the businesses in the space domain towards stable and profitable enterprises, with demanded products and appreciated societal contribution.

A slight detour - why is the upstream/downstream partition unfortunate

For some reason, the upstream/downstream distinction is a very popular way to talk about operations, companies, and investing in the space domain. I think it is rather unfortunate. Basically, the only conclusions you can make using this framework are that:

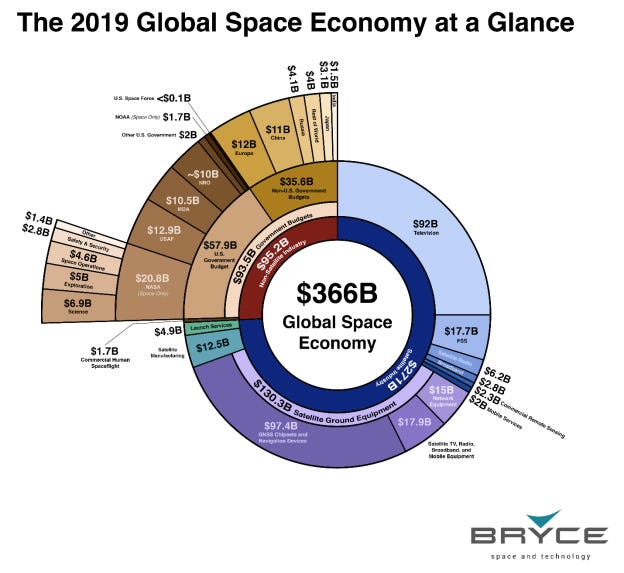

The majority of space economy volume comes from downstream - based on the attached (and ridiculous) Bryce tech graph - where a majority of those revenues come from paid satellite TV channels. You can see why the assertion doesn’t make sense here.

The second conclusion you can come to is that the “downstream” industry has higher margins, higher TAM and lower capex than the upstream component, of course, conveniently ignoring that you kinda need the expensive assets up there to produce the magic saas-like products down the stream.

The other holes in the simple framework are companies moving in either direction (think Tommorow.io moving from software “downstream” to satellite “upstream” or BlackSky trying to present themselves as a Palantir-like software that just happened to have satellites).

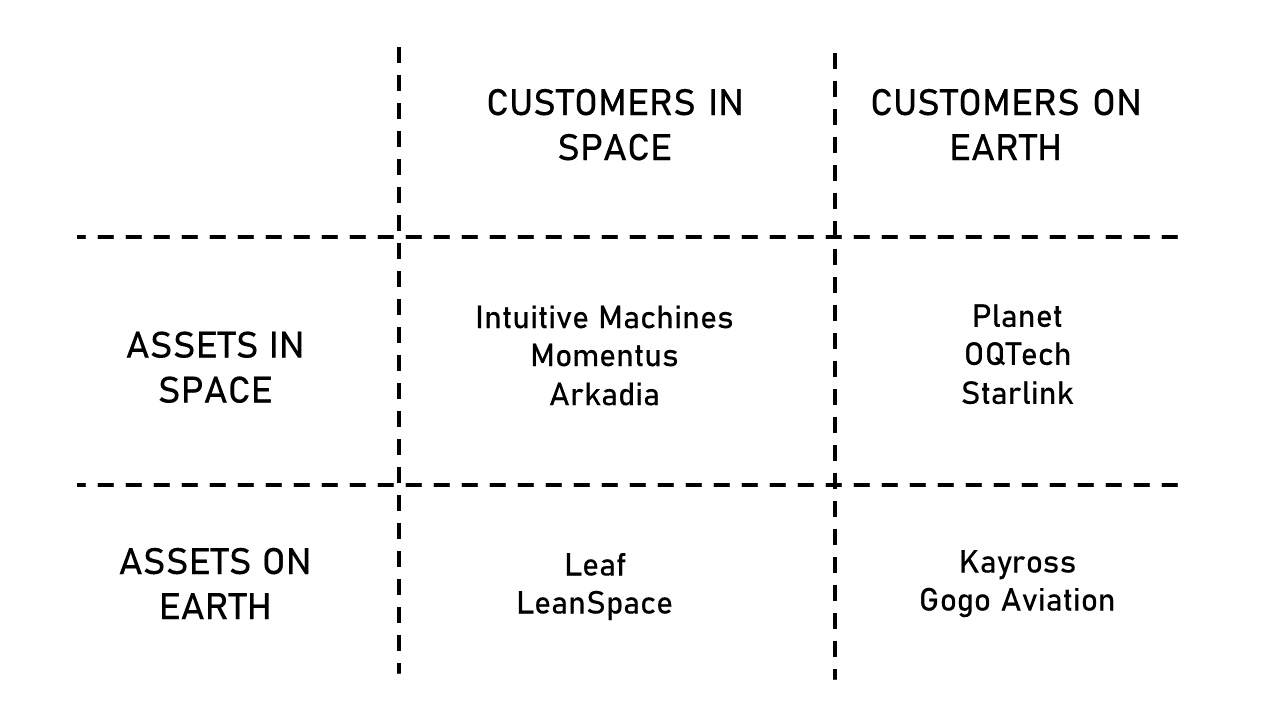

Another way to illustrate my issue - think of the following companies: Momentus, Planet, LeafSpace, and Kayrros. Well, the interesting thing is that Leaf and Momentus cater to a similar target customer, small satellite operators, as an upstream-downstream pair and Kayrros obviously shares more with Planet. Their executives would probably try to convince you very hard they are actually a SaaS-like business - similar to Kayross, yet using the original upstream/downstream they end up with propulsion manufacturers and lunar economy startups instead.

Here is what I prefer instead

A grid I use instead asks “where are the customers” and “where are the assets”. Graphics by Pushkar Kopparla.

I’d argue this model leads to bundling companies with more similarities - in terms of market structures they cater to (the axis between a single large customer - absolute reliance, to many small customers - no individual reliance), and how closely linked is their business to hardware assets.

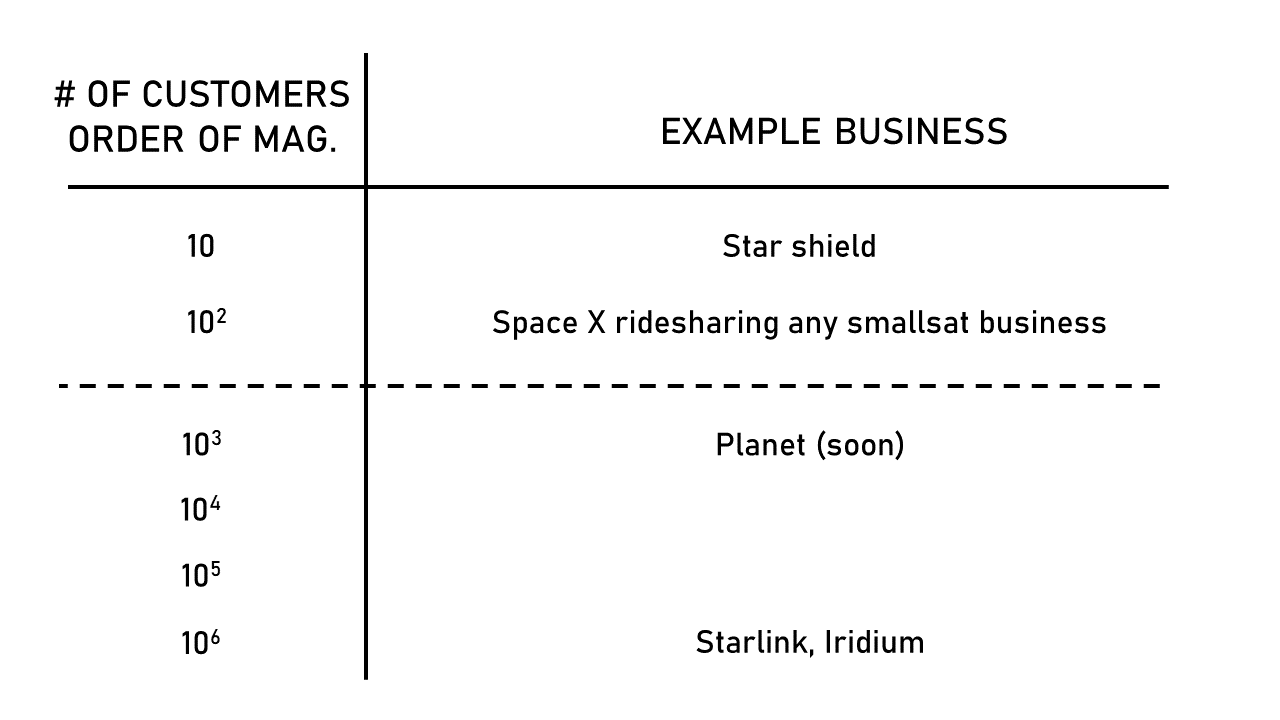

Axis of reliance - magnitudes of customers

Honestly, I’m surprised the discussion about the magnitude of customers isn’t more frequent. But, I would argue that whether your business relies on Usually, it comes up only implicitly. But obviously, whether your business relies on the ability to lobby for a single digit of large contracts or requires chasing hundreds of business owners up to potentially building/managing/monitoring partner/marketing channels matters a whole big deal. Customer magnitudes will come up further in the article.

Exits in the space industry

Investors in the space industry are here to make money. That also happened to be my day job. Apart from a select few already successful (or hyped up) deep tech companies, active secondary markets are not a common occurrence and so, investors rely on exits to generate the needed returns.

Those happen, simply put, in two ways, listing on public markets (IPOs) and acquisitions (M&A). A foundational part of my argument is that, with exceptions (Skybox Imaging and Swarm Technologies, York Space Systems publicly disclosed their exit valuations), industry M&A has failed to generate adequate returns for VC-backed space startups. A few unknown transactions could skew the balance, but nah, I don’t think that is the case.

The reason is, in part, that you need to have pure cash on a balance sheet (or access to low-interest debt) to be able to make acquisitions - which newspace companies have a notorious shortage of. In other words, new space companies are generally not mature enough to be able to conduct notable acquisitions. Secondly, every acquisition comes with an integration risk, which is larger for smaller companies. So the current subscale size of space companies doesn’t favor M&A behavior.

An attentive reader could now suggest that the majority of the newspace public market exits happened via SPACs at ZIRP and got valuation-decimated in the months and years since. Well, you are obviously right - but if we remove the set of space SPACs from the population, we might as well disregard newspace exits completely - as there would be only a few unreliable data points left.

To continue on this detour, let me talk about Europe for a second. We currently have two newspace companies eligible for (and in the latter case also in desperate need of) some form of exit opportunity. D-Orbit has attempted to go public via a SPAC in the past - around an EV of 1.2B. Regardless of where the valuation is now, it will be north of 500M… so now the question is, how many Europe-based players are big enough to conduct such a transaction…

ISAR Aerospace publicly speculated last year it might IPO in 2024. The reasoning is simple - nobody in their right mind would acquire ISAR Aerospace. At the same time, ISAR still needs some more cash inflow and in this case, IPO might be the only option. I will not end well, however. Back to business…

How to exit a company

So, now we know IPOs are the way to generate returns for VC-backed space businesses. We will not see the 2021 cadence for a long time, but can expect somewhere around 3-5 global space IPO events annually for the foreseeable future.

So for VCs, the right approach is to think about what a space company ready for public markets looks like and then reverse in time to the present state of an evaluated startup and think whether the two railway tracks can at least loosely converge in the future. In other words, to ask the question “Is there a foundation for this startup to be a publicly traded company within the next 10 years?”

A few years ago, I asked a very smart BofA banker about what sort of criteria they are looking for when bringing a company public.

Among some of the things he said were:

Experienced management team with relevant roles filled, good board governance

Significant, growing and predictable revenue (with profitability achieved)

Diversified base of credible customers

Differentiated customer proposition

Appealing growth strategy for the years to come

When VCs invest in companies, high-potential founders are what we look for in the first place. Other management and board roles will get filled over time. Revenue is really a function of building something customers want. Customer proposition and vision are what we cover in the initial analysis as well.

What I absolutely cannot overemphasize enough is the diversified base of credible customers.

Diversified means your business is not dependent on a concentrated number of customers - and thus if any of them churns, the company is not fundamentally at risk. Credibility refers to the ability of customers to contribute to revenue over a long period of time and not be at a constant risk of default.

I have analyzed space failures before and one of the most frequent traits is companies with no money referencing large revenue backlog promised from companies… which correspondingly also don’t have any money. And then the ecosystem looks like a massive lift-off, yet is so vulnerable to any small disruption.

And we are getting to the climax of the story: where do you find a diversified base (business model with a high magnitude of customers) of credible customers (existing companies with good payment ability)?

…

on Earth.

They are insurance, shipping, telco, automotive, pharma, energy companies.

One more time, summarized

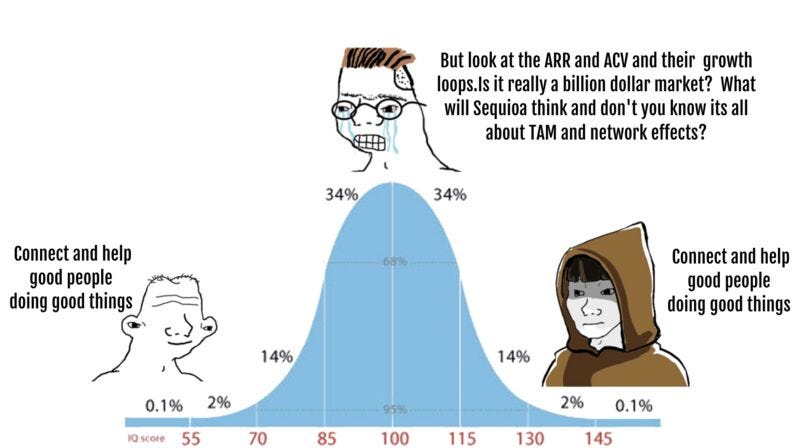

Financial investors invest in the space industry to generate returns. Those returns have been historically generated by companies entering the public markets. To be able to enter and function in public markets, you need a high magnitude of credible customers. Such customer bases you can generally find in products and services addressing the needs of customers in sizable markets on Earth.

Two differences

If you have finished the piece now and think “Of course, it is obvious” - well, I’m glad you agree! I’m not the only one who thinks this way. Several VCs in the space domain use the statements “we invest in applications of the space industry” and the “use of space for the benefit on Earth” is the most overused phrase right after “space is hard”.

More exact criteria

What hopefully develops my narrative further is that I both justify and explicitly state what classifies as space applications for large terrestrial markets.

When talking to startups, my first big question is, which big existing market on Earth does this cater to

Can this solution be sold to a large magnitude of individual customers

Needless to say, there are countless other ways of achieving success with a space company - just that those above states help filter ones that have, for me, the right risk/return ratio in a realistic timeframe.

Normative power

The second difference is that this approach not only positively describes how things are like, but adds a normative recommendation as companies may choose to act. Several companies positioned themselves, or are working towards precisely becoming a space to Earth applications firms.

AAC Clyde: satellite manufacturing → Space as a service (climate + maritime)

SpaceX: launch → Starlink (telco), starshield (government services), tourism (mass market)

Astranis: satellite manufacturing → dedicated microGEO satellites (telco) but also additional constellation for fractional capacity (maritime, aviation, government services)

There are a few companies I sadly cannot speak about, but you would be absolutely amazed at which terrestrial industries can space companies cater to.

So I think every space infrastructure business can ask → how can I get closer to the value creation for customers on Earth? If you know how to launch suborbital rockets → how about opening a service that offers microgravity experiments to pharma companies? And so often, as a VC, I meet companies that say “Currently, we work on [space infrastructure], but actually in the long run the real goal is [large terrestrial market]” - way to go!

A few more notes

Intuitive TAM estimations

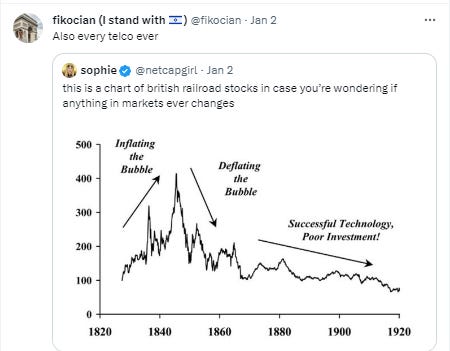

The saddest outcome for VCs occurs when there is a good team, successful market penetration, the startup dominates with the product/service… and the market is just simply too small for the startup to attain any meaningful valuation/revenue.

Sometimes I do this exercise with startup pitching to us… okay, so if I take you at face value, you have the best product, you absolutely conquer the market.. and you will serve to X customers at Y ACV per year yielding Z annual revenues implying V valuation… and that one still doesn’t provide a meaningful outcome to us.

What often boggles my mind is that for many industries, investment flows are not even loosely proportional to their market sizes. Global Satcom market on the worst day is still some 10x larger than the potential of the OTV market on the best day. There are many holes in this rough estimation, but at least on a rough calculation level, I found Intuitive TAM estimations as a pretty useful tool.

This is a quick and dirty slide I once fixed to demonstrate the large terrestrial markets approach. The more companies I know, the more I am I able to find fabulous ways to help real people and companies on Earth. So when thinking about the future of investing in the space industry, this is where I hope we will find it.

Counter arguments

There is a range of very valid counterarguments to what I wrote above. I wanted to note down and, in some cases, discuss some of them.

Markets not as big as they might seem

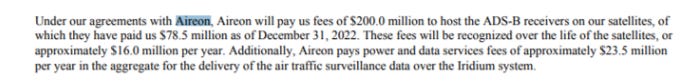

The most valid counterargument is that some markets are not remotely as big as they appear. I’m a big fan of a company called Aireon, which operates auxiliary payloads on the Iridium Next constellation and is a global leader in satellite-based ADB-S. With some 40 thousand planes in the world and 100 thousand flights conducted daily, one would expect satellite aircraft navigation to be a major business opportunity. A few startups are betting on the market (Startical, Skykraft, Head Aerospace), but so far it doesn’t seem like this business is cutting it for Iridium. So often markets that appear huge might actually not be so.

That also has to do with the law of large numbers. Taking the above 100 thousand flights as an example, annual flight hours multiplied by basically any constant will result in a large number on paper, but that might have a little connection to reality.

Power law game

In the article above I try to offer a general recipe on where to look for valuable space companies and how such a space economy could look like. Funnily enough, VC is a power law game and investors should thus care little what general rules say, precisely because they do not matter for building off-charts companies.

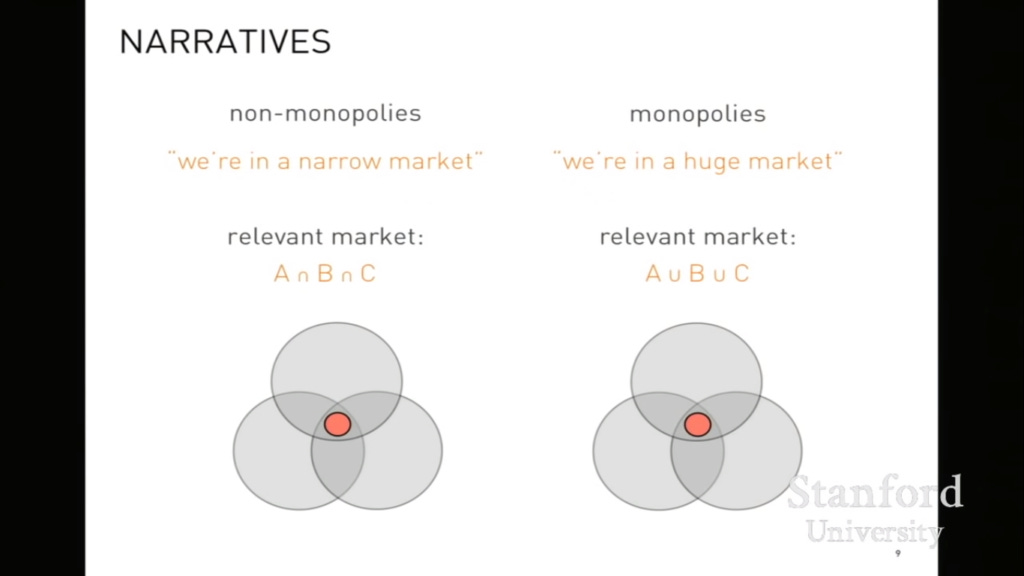

For years, Peter Thiel’s Zero to One would be the closest book on my nightstand. Thiel would certainly dislike my argument for the necessity of addressing big markets and suggest instead to start with a monopolistic share of a small market. In addition, companies have no incentive to be transparent about their market position.

Shall I commit blasphemy and disagree with Peter Thiel, I would argue that the companies Founders Fund incubated/successful unicorns started as small markets, which however were parts of huge industries.

Netflix - big DVD rental business, monopoly on small digital streaming business -> part of an already huge media/entertainment industry

Airbnb - only players on sharing short-term places, part of a large hotel industry

SpaceX - one of a few startup micro launchers, part of a non-negligible launch contracting business

Anduril - monopoly on a software first robotic submarines - part of a huge global allied military spending

For space startups - obviously, large markets are already dominated by enterprise players, the goal is really to find a niche/non-existing product/service/improvement which however has the potential to redefine an existing category.

A long path to revenue

This whole article is a result of a meme I posted in September 2023 and the resulting discussion. In which Prateep notes that the “applications” part of the business has an equally long path to revenue to space infrastructure. The example cites EO - the timeline would certainly be longer for applications like maritime connectivity requiring licensing and hardware installation.

Where space is differentially better

Chasing high-contract values

This might be the biggest hole in my narrative. While stock markets love high-margin recurring revenue, companies often do precisely the opposite. I have heard way too many rumors about one SAR company that couldn’t figure out how to sell its data product, so they sold satellites instead. It is certainly the best way to boost the “revenue” column in financial statements.

In the same way, RocketLab got a historic 515M contract. I can only imagine how long it would take to create 500M of value for terrestrial customers if you can just get 515M by winning a single contract. Companies pursue the paths of least resistance and till there is such access to single-source high-value contracts, there is little incentive to chase customers on Earth just because Filip suggested to do so.

As this whole article has been about, the above approach will not lead to the long-term stability the financial community likes… but the visibility of 0.5B in revenue has indeed some seductive power.

Have I played by my own rules in the past?

Not really.

Picks and shovels approach

While some VCs like “space applications” others openly advertise they invest in the “picks and shovels” of the space economy. While I broadly do not prefer this approach, it carries several valid points

For investors with an aero(space) background, investing in what they invest in is the natural and most logical choice. If you worked at SpaceX and now transitioned to VC, logically you will be closest connected to space-grade hardware.

The other strong argument is that we don’t know which particular thermal EO or narrowband IoT company will cut it - but they all will need the same launches, buses, and solar arrays. For larger VCs, that can be covered via some degree of indexing (investing to multiple companies in each application vertical), but smaller ones might prefer to pick the picks and shovels approach. But again a main issue may arise as I described in the “Intuitive TAM estimations” section.

Cheap products, big markets, not both

Now I might be getting too esoteric. Another hole in my narrative is that cheap products and big markets are usually opposites of each other. EO for insurance/stock market trading is a best example for this. If you use whatever EO data for hedge fund trading, you make big returns and pay a large price for a small amount of imagery. Your moat becomes public, others begin to buy the same imagery. Large volumes, low prices. But since everyone has access to the data, nobody makes differentiated returns, the imagery is a commodity and the market becomes small. Congratulations.

This would make for a longer discussion - but I just wanted to acknowledge that big markets, good investments and proliferated products might have not been as connected as one would think.

Asteroid mining

Another hole in my narrative. It somewhat doesn’t exclude asteroid mining, which I consider a rather ridiculous endeavor - especially if companies voyage on the same trip which failed many times before, without a substantial strategy change or immediate revenue stream.

Just to make the argument explicit - we can say that a space company that wants to mine asteroids is actually a company that serves a large terrestrial market (either mining or manufacturing, depending on a strategy). So I either need to change my opinion on the entire narrative to begin to like asteroid mining. Two considerations that might make me less conflicted: with Starship, asteroid mining might actually appear sane. Secondly, a few companies addressing the market tonight have overfocused on the academia/civilian government customers making it indeed a space infrastructure business.

A detour - how startups become corporations

As companies scale from startups to mature companies, they acquire new products, either via internal development, an acquisition, or most likely a combination of both. SpaceX did this with rockets -> internet -> government services. Rocketlab did this with rockets -> spacecraft systems. So, another hole in my narrative is that the first tackled market is rarely indicative of how large the company can become in the future. The caveat to it is that sizable vision is very closely linked to the ability to attract funding and talent (!) which makes it difficult for marginal improvements to grow into substantial businesses.

Difficulty for startups in the space domain

I will probably address this in a separate post later on, but a few trends establish a much more difficult landscape for space startups: sovereign space, corporate innovation, and national space champion doctrine.

Reminder

—

It is nice to be back! Thank you - dear subscriber - for being patient with me. Time flies and only now I see I wrote my last piece in June 2023! I moved to Stockholm and wrote this article during a couple of lovely flights between Paris, Stockholm and Helsinki. As for the unexpected delay… it is a poor excuse but I have been really busy with what I preach - addressing issues at the intersection of space, finance and strategy in my investing, M&A and advisory roles. I have a couple of strong pieces in the pipeline, hopefully on a stronger cadence than you have seen from me in the last 7 months. A reminder: I’m pretty accessible and my contact details are public - get in touch if you wish. As always - thank you for sticking around!

Good read, very interesting approach. My two cents ? Telecom Rules !