The year of spacecraft failures. Second in the row, and why nobody seems to care.

Don’t say it, don’t say it, don’t say it… space is hard.

Here is a list of several space companies - they all have something in common. It’s quite a long list. SpaceX, RocketLab, Relativity Space, Firefly, Virgin Orbit, Launcher, SES O3b Networks, Intelsat, Viasat, Inmarsat, HE360, Capella Space, OHB, Intuitive machines, Astrobotic, True Anomaly, RFA, Spire, Atomos Space, AAC Clyde, Astroforge, Astranis, ClearSpace, Starfish, SatVu, iSpace, Space One.

During the last two years, all the companies above, by fault of their own or not, suffered from and publicly acknowledged a space hardware anomaly, ie their spacecraft didn’t work or majorly underperformed expectations, didn’t deploy or suffered from a launch anomaly. I originally wanted to write this piece after 2023, but last year things got no better so I have even more material to write about.

I have a collection of roughly 30 anomalies—more than one per month—representing billions of dollars in hardware write-offs and much more in lost revenues. Only a few notable space companies avoided any unlucky events, and in reality,, the number is even lower as many issues remain unreported.

Media reports do cover those failures, but unfortunately, they focus mostly on quick reporting of: X piece of space hardware fails, here is who to blame, stock is down XX% or xx% of workforce will be cut down” or “investors are unhappy”. Seeing those are no isolated incidents, I think there is a space for a more substantive analysis and in the following piece, I will try to suggest answers to

Are we seeing more failures now than in the past

What could be the possible reasons

What are the consequences of failures on companies and the ecosystem more broadly?

In light of the above being true, what can/should you do about it?

Personal anecdote

First job in my career I was the lowest-level intern at SAB Aerospace, a small aerospace subcontractor in the Czech Republic. SAB’s major project was a small satellite dispenser (SSMS) for the Vega C launcher. I started working there on 10/2018. The SSMS PoC launch should have been basically imminent.

After much delay, the prior in-line mission launched in July 2019 - and it was the infamous VV15 carrying UAE’s major military satellite Falcon Eye 1. Thermal protection on the launcher failed resulting in a total mission loss some 9 minutes after the launch. The aftermath included massive insurance payout for the end customer and more than a year-long pause for Vega launches. The UAE government is also no longer considering launching its military satellites on the Vega launch vehicle.

I got to finally see the SSMS PoC launch livestream some two years later from the basically imminent launch date during VV16 in September 2020, though living in a different country and working for a different company.

Some disambiguation and disclaimers

This is obviously a tricky topic, opinions are my own, in cases where I identify companies, I generally rely on publicly available sources.

I will use “failure/loss/anomaly/malfunction” and “spacecraft/space hardware/satellite” somewhat interchangeably.

There are different modes of failure - the suffering company is not always at fault, there can be third-party causes or acts of God. That said, the suffering company still ends up losing hardware and revenue, regardless of who is at fault - which I try to write about. Unless explicitly acknowledged, let’s assume the cause is external.

Of course, there is also a strong incentive to blame the causes on external entities. I suppose an interesting aspect of leading commercial entities is the necessity to control for issues outside the company’s direct control.

I make a somewhat poor distinction between small/partial/major failures and total loss - typically the cases above refer to a total loss but in some cases, the companies derived a partial revenue stream or an alternative use case. Once again, it is difficult to judge the severity from an external POV unless the companies are publicly listed and quantify the loss in very exact terms.

That said, I report mostly on cases self-disclosed by the companies - either due to a transparency commitment or shareholder obligations. There are of course many additional industry rumours about “those data being sh*t” and “that sensor is not working because…” or “I was working with a company that had a payload on that satellite and it did not really work.”

No discussion on space failures is complete without talking about insurance - the few insurance providers/agents/brokers in the space industry do I think a decent job explaining their process and market - my knowledge of the sector is quite limited on the other hand so will touch it only tangentially.

With that out of the way, let’s get to it, shall we?

Do space failures happen more often now than they had previously?

There are two ways to look at it. One of them would be to just take an absolute number of space failures, the other one would try to measure the stock of failures as a proportion of the total industry activity.

That, of course, introduces two issues, measuring the total industry activity and condensing failures of various kinds into a single number. How do you accurately assess a partial failure or an expensive hardware failure of a company with a flawed business model?

For all of their flaws, for the cumulative space activity there are some value-add method estimates. For the failures - the best data probably comes from insurance companies, who have access to a lot of non-public data as well as an incentive to accurately assess the actual extent of a failure in monetary terms.

The issue is that data quality varies vastly between space industry sub-segments: :

For GEO satcom, there is a long-standing benchmark and quite some transparency also towards China-based operators. A few Western consultants I know who do tech DD for insurance companies have worked with Chinese operators as well, which is typically not the case for other areas of the space economy

For launch, the success failure distinction is quite binary as well - AXA space risk update data suggest the failure rate has been quite stable around 6% between ~2013-2023. While established launchers get to achieve progressively better reliability rates - new launchers coming online successfully cancel it out.

On the other hand, small satellites, once in orbit, are really an obscure part of the market, largely uninsured, and in the long tail outside SpaceX/OneWeb/Planet/Spire largely operated by non-public companies making any data collection barely possible. “approximately 97% of the ~10,500 active satellites on orbit are uninsured.” (link)

When we dive deeper into the failure frequency:

In absolute numbers, there is ever more space activity happening and consequently, a stable proportion of malfunctions can appear as a massive spike - unsurprising given the industry activity boom. This is much similar to the aviation industry in two ways

A lot of activity in general is happening. A very small fraction of those result in critical events, a very small fraction of which results in tragedies. Those result in major coverage.

After a few near misses, the community/media are more alert towards new mishaps and incidents - making an impression of ever more failures.

Space companies seem to be much more transparent with spacecraft anomalies. Astrobotic might possibly have been a trailblazer in space, “setting a new standard for space mission transparency” (NASA watch, link) in January 2024.

This is the first tweet in the series of mission updates following the ULA launch, from Jan 8th 2024. Link

Similarly, the landscape of media covering the space industry is changing. Historically, it has been quite a small market resulting in a small circle of insiders covering the industry. Some of them (Peter) ask hard questions, most of them really don’t. With a growing number of firms and changing structure, a few media outlets (like Payload) emerged and more existing platforms gave space a more consistent coverage (Techcrunch, Sifted; WSJ, FT). Together with a rise of independent platforms (like substack), few (mostly) young and ambitious journalists are consequently able to pursue more critical topics - resulting in an increased coverage of malfunctions once again.

Finally - spacecraft failures are not limited to the Western world. Iran and North Korea of course face their challenges building space programs against international sanctions. But even in China, at least on the launch side we see failures of companies like iSpace and SpaceOne and Galactic Energy - where CGSTL for example lost 3 weather satellites.

If more failures are happening, what could be the reason?

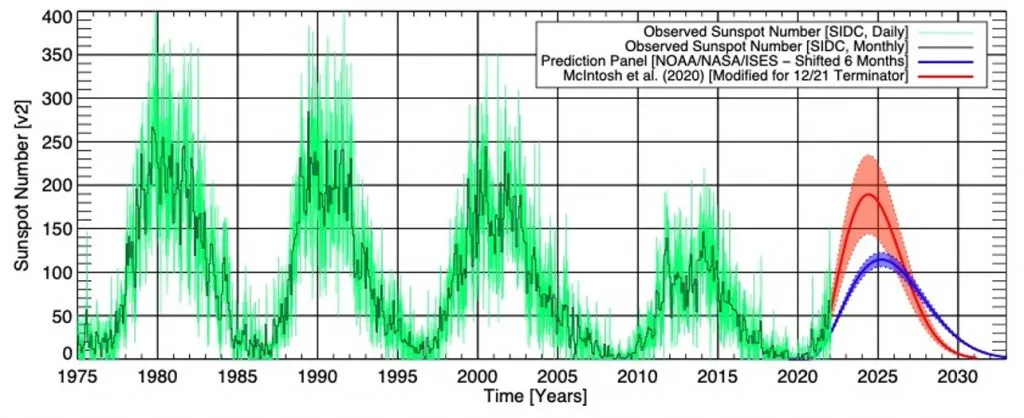

One actual physics-based reason might lie in the solar cycle:

Link: NASA Solar Cycle 25

I’ve heard varying opinions on this and don’t have the tools (physics) to verify myself. But on a ground level, activity of sun varies with ~11 year cycles and at its peak produces a lot of solar flares and solar wind - charged particles flowing towards the Earth and posing a risk to electronic systems of satellites + interacting with the top layers of atmosphere contributing to faster satellite deorbiting. The new space industry caught a second wave in ~2015 or at a time of solar activity bottom. What might have worked then might go through challenges now.

SpaceX first lost 40 satellites but then performed better later on. HE360 and Capella Space reported issues too. The Capella Space later shared an academic paper on their response as well.

In most of my writing, I keep coming back to 2015 when a new wave of enthusiasm entered the industry (not that I would know) following the SpaceX series G and major exit of Skybox Imaging to Google. And that energy ripples through time and results in a lot of new companies being created. For a long time, they stayed mostly in PowerPoint mode, and somewhat, in the last few years a lot of new companies are finally setting their hardware on a date with reality. Results are sometimes explosive.

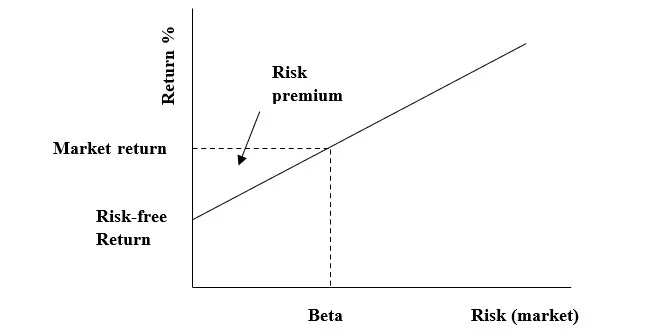

That reminds me of one of the foundational concepts in finance, the risk-free rate.

Quite unsurprisingly, it suggests that you can never get a higher-than-average return without accepting a higher-than-average rate of risk. And that of course applies to spacecraft engineering as well. Most of the space engineering knowledge and culture still comes from high-end one-off long-cycle high-reliability projects, for arguably very good reasons.

The former space industry structure resulted in a typical satellite infrastructure approach of multiple backup systems, high redundancy, and thorough testing - as there should be for 100M+ missions. That of course comes at a cost - which new space companies tried to eradicate. The mean failure rate increases, although with high dispersion as well. It leaves some companies extremely lucky and with a few functioning cheap satellites they can raise enough money to keep working - for others, it might backfire horribly.

My favourite movie is Law-abiding Citizen and there Clyde Shelton says “you can’t fight fate” and in a similar fashion I’d like to suggest that you can’t fight the risk return trade off either.

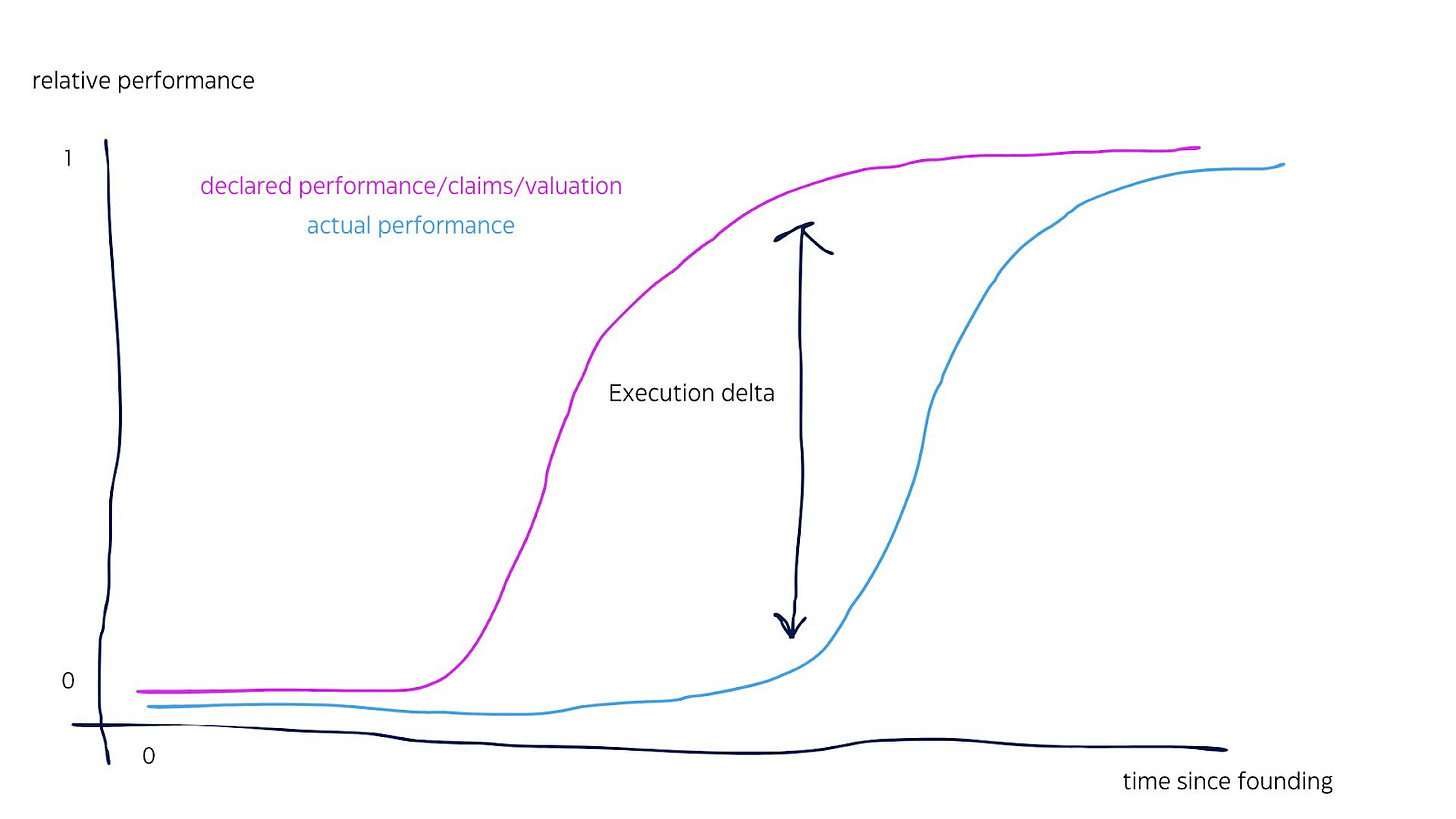

A useful additional question to ask is whether the goals are actually the same. Because in the first wave of space startups, space enthusiasts were the main class of founders and there was a high degree of fundamental care and belief that working hardware early will lead to a positive feedback loop with riches, fame and a better world at the end of it.

For the new generations of space companies, especially if based in El Segundo and part of the American Dynamism, I’m often not quite sure if working hardware is the goal - often it feels that publicity, activity, generating milestones and showing progress take priority. “Move fast and break things” applied to the space industry.

Sidetrack: space is still an ancient industry

Space is still a comically obscure industry. People talk about the mythical 1T space economy and widely proliferated satcom, eo, PNT, space manufacturing and whatnot. But then, every week I will heard a few horrendous stories like

A company wants to ship it micro launcher to finally go to space but its home country doesn’t know how to export license one and the receiving country has never issues an import license to one

Component advertised as “in stock” with a lead time of 9 months.

A pre-seed company having to mount its sensor on an OTV some 3 months before shipment to the US launch site which takes place 3 months before the launch so half a year of depreciating hardware with no data generated

LEO satellite with 6 months commissioning time, or 1/10th of a 5 year lifetime

Spacecraft operator contacting 9 micro launchers to launch their spacecraft of which only 2 responding.

(Someone is literary trying to pay you money to launch their satellite on a launcher you’ve spend 10s-100s millions of other people’s money to built and you are not bothering to respond?)

A company losing out all growth for a year because one mission got shifted by 3 months because one launcher failed.

Spacecraft stuck on orbit for 6 months months because being a stalking horse for the first ever commercial reentry license

People unable to find their satellites after Transporter mission launch

What do you mean you spent 10M on a satellite and you can’t even find it

Multi-hundred million mission failed because of a valve

So, my sideline is that new opportunities in the space industry open as much with lowering launch costs as they come with eradicating all of the self-inflicted pains described above.

What are the implications of failure for companies and the larger ecosystem

At first glance, the implications do not seem to be so severe. Of the companies that experienced setbacks, most of them are still here, quite a few of them are thriving.

Interestingly, hardware malfunctions do not seem to be a big concern for the VC community, especially in the us. I spent unhealthy amounts of time plugged in with other VCs and reading every space investment rumour out there - but I can’t recall one VC that would mention a concern over the mildly alarming rate of space hardware failures.

For a bystander looking for a quick dismissal, saying “Well, but none of your satellites actually work, lol” would be a perfect roast of the industry. I can think of two reasons why nobody is bringing it up - partially because it wasn’t discussed much, partially because those who know don’t want to say it and those who are not invested enough might not notice.

That said, there are consequences to failure and they eventually start to play out - just usually behind closed doors. The show is in downrounds, ugly structures, executive changes, key people leaving. But not for all companies equally.

In 2015, Paul Graham wrote an essay Default Alive or Default Dead which became very popular during the 2020 pandemic:

“When I talk to a startup that's been operating for more than 8 or 9 months, the first thing I want to know is almost always the same. Assuming their expenses remain constant and their revenue growth is what it has been over the last several months, do they make it to profitability on the money they have left? Or to put it more dramatically, by default do they live or die?” (link)

And I think that provides an excellent framework to think about how hardware malfunction plays out.

Default dead: From hindsight, it is easy to see Virgin Orbit operating on borrowed time from the start. After its 3rd launch and a 2nd failure in Jan 2023, it was quite apparent the company was going down under and no one bothered to take over even the remains. (Though for many players, the equipment discounted to a few cents per dollar came in handy).

Some companies are very good in faking this - after a failure, their announce a larger and a more ambitious product, continue to hire new people, bring high-level additions to their advisory boards and figure out some shiny way to show progress - but of course, companies life on a borrowed time and if you stretch the bullshit gap too much, it’s gonna come back like a boomerang.

In English we say “ you can’t fight fate” and in Czech we say “Boží mlýny melou pomalu, ale jistě”

Default alive: AstroForge is a CA-based asteroid mining company. In 2023, a solar array reportedly did not deploy on their satellite. In 2024, the company raised 40M Series A towards its second launch. SatVu is a UK-based thermal EO upstream constellation. Their first satellite by an external player malfunctioned. But it was insured, the company managed to raise some extension funding and bring two more satellites to life and the company lives on to fight another day.

And then, of course, there are companies in the middle - and their hardware anomalies often become a catalyst for change that might have needed to happen for a longer time. That said, as I wrote before, space companies are unusually resilient and the promised consolidation wave never really came - so in space of failures, companies usually find a way to scrape by.

Listed companies

With new space companies becoming publicly listed, occasionally we get to see the market reaction play out in real time.

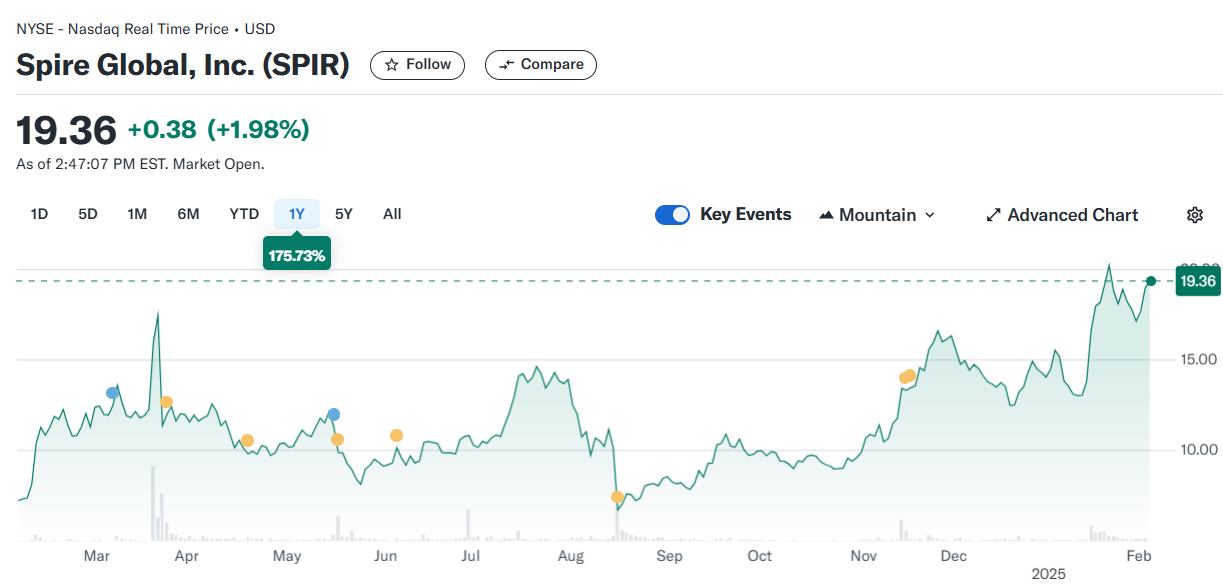

Spire’s shares did go down about ~34% in August 2024 because of the underperformance of hosted mission for NorthStar and Space, a Canadian SSA provider. Solid discussion by our friend Case is to be found here.

Creotech is a satellite manufacturer based in Poland which launched an EagleEye satellite on Transporter mission in August 2024. There have been some issues with the satellite which resulted in traders erasing some 20% of its market cap.

The future growth expectations matter. I don’t have a detailed analysis but the stock market reactions to announced GEO satcom operators asset failure sometimes lead to significant market reactions, sometimes not so much.

That could be an accurate estimate of the failure’s impact on cash flow generation

Possibly because for heavily indebted operators a lot of the market reaction plays out in bond markets which are less straightforward to read

Investors broadly don’t have high expectations of the business and so any failures do not deviate much from expectations.

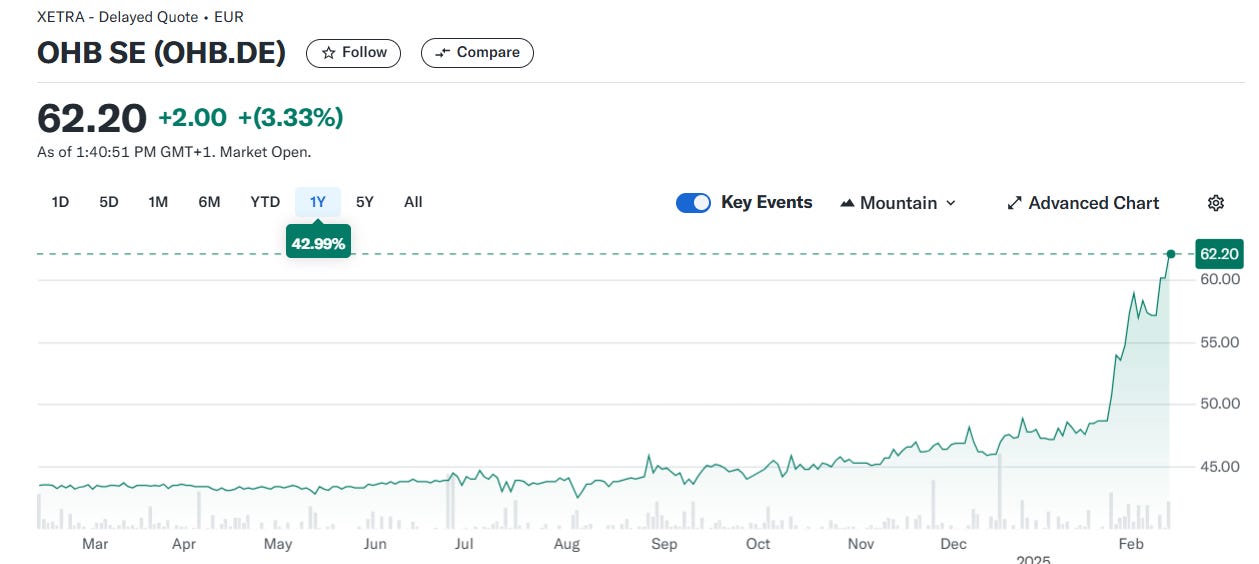

Stock market reaction on failures can also help us assess how a strong financial backer affects company’s volatility to inevitable space failures. For the last two years or so, OHB has been in a process of a minority take-private transaction with KKR, where the Fuchs family will remain a major shareholder but KKR will purchase rest of the shares and delist the company. The minority buy-in has happened as I understand but the company is in a no rush to cease trading.

In August 2024 news came out that the two SARah satellites built by OHB for the German Armed forces do not really work. There is a slight spike in trading and price decrease, but not really a significant one. As companies across industries stay private for longer, the trend will be no different for space companies. And on the benefits is that a private owner with longer time horizons can shield companies from post-failure market volatility.

Apart from public and private markets investors, the government is a major shaping force of course. Multiple analyst expressed surprise that Momentus is still operational and publicly traded, but every few months, the company gets awarded a contract similar to this one effectively being extended a continuous lifeline. I can think of at least one more company that got a MM USD handout just after a high-profile failure.

One of the key questions is - how many chances will be extended to you before investors and customers give up. In ~2010s, SpaceX succeeded in launching Falcon 9 on a fourth attempt. Today, I’d guess investors are bit less forgiving. One failure seems to be okay, second is stretching it, third one is on edge and the fourth one usually means game over.

Anomalies occur - what does it mean for you?

I hope this piece will become a part of a open, useful and important discussion on why failures happen, what are the implications and how to avoid/deal with them. Some thoughts below.

Understand your positioning

A friend of mine runs an EO company - they launch with unproven launch vehicles, unproven deployers and cheap satellites. They told me - “I know what we are doing. The chances of failure are predictably high but that’s our positioning, even if the first four satellites fail, we will still be better off than launching an expensive satellite of the kind with a proven launcher.”

The testing policies and risk profile should be aligned to the fundamental strategy (low cost x premium differentiated products) of the company.

That said, sometimes the decisions are just unwise. I track rumours of companies that raised 100M+ kind of rounds losing their satellites after skipping basic ground tests.

Allow for failures

Failures are inevitably set to occur. Planning one step ahead via what if scenarios is a good way to keep the company in the default alive bucket. But of course, many industry leading companies have succeeded in “we have one last chance” type of scenarios.

This is an exercise I keep doing quite often. “Okay, let’s think about this. You do this, Either A or B will happen. What impact will A have on your company? What impact will B have on your company? Which impacts are immediate - and what will be the impact in the next 18/24/36 months? How will that affect your sales, hiring and fundraising?” Just thinking though how decisions now might impact the future - basic exercise of course, but it often ends up being quite helpful.

Communications

A company I know sent the following email before their first launch. It approximately read like this.

“We are launching to space. This is the situation. This is what we are trying to achieve. Those are the risks. Those are steps we took to minimize risks. If the mission succeeds, we will learn this. If the mission fails, this will be the impact and those will be the next steps we will take.”

Unsurprisingly, the company is doing well - because they planned in advance, considered what if scenarios and communicated that clearly to their investors. 10/10.

Seize the opportunities

“The story I’ve heard is that we had 85 problems during the course of the mission… we were able to solve them… our high-gain antenna was pointing at the surface of the Moon. What we learned is that we could still close the link and take off the payload data. We actually got an inquiry from NASA to be able to characterize the multipath.” Said Craig Moll of Intuitive Machines at the APSCC 2024 conference (link).

So they actually find a way to recover from the setback and then sell (!) to NASA the recovery method. Pretty impressive. The wave of setbacks in our industry opens a path for new business opportunities.

Offering a solid crisis/troubleshooting support package should be a bare minimum, but is a way to increase customer retention, differentiate from competitors and maybe even bring in some recurring revenue

High-reliability launch/OTVs/components warrant a premium, as do bespoke launches not dependent on a longer easily disrupted queue.

I’ve heard from an ISAM company that their failure actually generated so much press attention to raise the successive round.

Consider getting insurance

I don’t have a strong visibility into the topic - but as we established, the majority of LEO satellites are uninsured. That is likely due to expensive policies, difficult processes and a lack of awareness/willingness/resources from companies to purchase one. And of course, at the beginning, it is an expense sometimes difficult to justify - and often it cannot be issued/meaningfully prices for satellites built in-house. But to a few companies, it was an absolute lifesaver.

Change of operating models in the industry will equally change the way anomalies impact businesses. Progressively more companies split apart the “building” and “operating” functions - with external infrastructure builders and/or operators, the risk is actually shifted away from the end service provider.

Additional notes

In 2016, Martin Langer, now the CEO of OroraTech wrote this paper, It’s very readable, bit old and someone should absolutely write a 2026 update. Link

D-Orbit has an impeccable flight heritage for their ION OTV. As an underdog European company their succeeded where many well-funded US companies failed. They must be doing something right.

I also wrote the “How Space companies fail?” I wonder why is it always me writing about such morbid topics.

Sometimes, failures/low reliability have far-reaching industry/national security/geopolitical implications. The whole saga around LCTs and PWSA constellation is a great example.

How projects that require significant political capital, failures come with very negative public reactions. Spaceport Cornwall being one example.

Hardware malfunctions have send companies over the edge in the past as well. HeliosWire or Hiber would be examples of that.

Culture is important - I think of a recently acquired European business that took a downturn in their reliability following a bit of contentious post-merger integration.

The surge in spacecraft failures (30+ since 2023) underscores why platforms for space weather forecasting like our https://mission.space are critical.

Space weather forecasting isn’t just about solar cycles—it’s operational survival. Real-time solar wind data integration allows operators to adjust satellite orientation, delay launches during radiation spikes, and harden systems against particle storms.

Thnx for the post!