Think simpler. Musings on space business models, market estimation and lessons from Silicon Valley.

Why simpler businesses are better.

Okay, folks, here is a thing. I spent my whole professional career convincing people that space business is a really complex, complicated matter (and if you pay me money I will make it a bit simpler for you).

In my VC work, I essentially convinced my seniors that this whole space domain is complicated and if they keep me on the team, I help you navigate it - and by extension deliver a better investment performance - which is the only way they can justify the expense of me being on the team

In my advisory work, I essentially say the same, space business is complicated, but if you pay me money I make it a bit simpler

Today, I’d like to go against that and show how quick proxies can improve understanding and evaluation of business models of space companies. As a reminder, one of the overarching themes across all my work is that better market understanding and better use of finance tools leads to better space businesses, which by extension, help realize the massive potential space companies have to (a) let’s not kid ourselves, make a sh*t ton of money and (b) help improve life on Earth.

/PSA: Hi team, welcome back! Especially if you are coming from Case’s, John’s or Will’s Substacks. Just a note I will be in London from Wednesday 26th June till Saturday 29th of June. If you are around and would like to meet up, shoot me a message./

Part 0 - Simple vs. Easy

At the start - I want to highlight the difference between simplicity and ease. Through the text, I will point out that most of the space businesses can be simplified to a simple algebra, and that such a level of understanding is required for good investment decisions and useful business decisions.

That is, however, not to say that space business is easy. Starlink is a good (and obvious example). As I will show later in the article - the revenue math is very simple. The promise is simple too: fibre-like connectivity without fibre / high-speed, low-latency broadband for everybody. But on the way there, Starlink faced several very difficult-on-its-own roadblocks to unlock the final promise.

If you cannot simplify a business to its core equation, keep digging. Or get somebody else to do the digging for you.

Part 1 - Actual Case Studies

Let’s get straight to the point. Here are some quick proxies for Launch, OTVs, Earth Observation, GEO Satcom, LEO Satcom and GSaaS business models. After that, I will try to discuss a bit of context.

Launchers: You can find this number publicly - SpaceX’s Falcon 9 price tag is about $75M. SpaceX has done about 100 launches last year - so the launch revenue could be 100*75M = 7.5B. Realistically, the Quilty guys suggested F9’s cost is in the “mid to high teens”, so assuming 20M, and guessing 50/50 split that is 50*20M+50*70M = 4.5B - certainly in the right ballpark, Payload predicted a bit higher number. Just to reiterate, I’m not trying to make any precise estimate, just a way to get a good idea of a company’s economics in like 30 seconds.

Knowing the numbers for F9 leads to a solid understanding of the launch cost base for small satellites. Most of them are being launched on F9’s Transporter missions. Let’s assume the cost is still the reported $75M per rocket. Transporter satellites may transport anywhere from 50-150ish satellites, 80 will be my number. 75M/80 satellites = c. 1M per satellite. If we now benchmark that to the Starburst report, which suggest 16k/kg for 50 kg satellites and 10k/kg for 100 kg satellites, which is in the range of 0.8-1M per satellite indeed.

Now, let’s compare it to RocketLab. They advertise a price of 7.5M per launch, max payload capacity of 300kg, which yields 25k per kg. Why is it more expensive? Well on the customer benefit side, it is a dedicated launch, so you can select precise orbit parameters + have the launch somewhat on your schedule. On the cost side, RocketLab produces lower volumes than SpaceX leading to lower benefits of scale + the non-recurring engineering cost needs to be split over fewer rockets.

Understanding the spread now helps us understand the business case for OTV. Let’s say you have a pure OTV and no advanced services on top of it. What is your price range? Well, customers chose between a dedicated launch (25k) or an OTV+ rideshare (10k+x). The X < (25-10k), thus x < (0-15k). So ultimately any OTV business projection needs to squeeze into this spread.

Now, let’s think about EO. Let’s say your whole satellite costs 5M (incl. launch) and stays up for 5 years. Extremely oversimplified, that means each year basically you need to pay off a 1 year worth of capex which is 1M, let’s say you sell imagery to defence which pays 1000 USD per image. So every year you need to snap some 3 pictures the defense will pay 1000+ USD to pay off the satellite and then everything on top of that pays your operating costs, overhead and finally starts making profit. Magic.

Or maybe a different way to look at it - the core question for imaging businesses is “are you able to make 5-10k per day per satellite”? Not impossible, but not easy either. Obviously different sales channels, tiers of imagery, archives, subscriptions, platforms, and products complicate the story, but this again serves as a useful proxy. To add to that - the timing is a big issue here. Basically, you need to sell at last the daily operating costs operating costs (Ground segment + mission control) /number of satellites, per every satellite you use to not to accumulate loss and at least some 3k of imagery every day after the commissioning phase to justify the capex expense you made.

This is a good time to mention how I became a Linkedin superstar - imao, getting 27 likes on a niche comment about EO pricing strategies is the space industry equivalent of winning Euro.

A few weeks ago Tom Segert of Berlin Space Technologies pointed out that Satellogic sells probably less than 1 day's worth of imagery in a year. It turned out into a pretty interesting discussion - my contribution was that there are very different strategies. Planet and Satellogic were founded really on the idea that there is large unfulfilled demand for EO assuming the price can go drastically down. Pleiades and Maxar still continue with the old - a lot of money for very little imagery. And so far it is quite clear which model is winning.

GEO Satcom. For a big GEO satellite, you need to consider the costs of satellite manufacturing, launch and insurance. Let’s say all together it is 500M. Big GEO satellites will make somewhere around 30-100M a year in revenues. So let’s guess you make 50 and we omit an unforgivable mistake of assuming no time value of money. At 50M, 10 years you are at 0. At 50M and 15 years, you are 250M gross profit which is very nice. If your satellite fails at year 8, however, you are in big trouble. Conversely, that also shows the reason why the idea of on-orbit repair is so attractive - if you can pay anything less than let’s say 40M per year to keep the satellite running for one more year, you prolong the revenues at the time the asset is usually already paid off. So the potential business case is still very attractive.

For LEO satcom, well - Starlink said that they have 3M subscribers. At 1000 USD per year (=a bit under 100$ per month) that is 3B USD per year. In reality, the number is higher because the estimate above doesn’t include hardware and a lot of much more expensive variants of Starlink (Maritime, Aero, Gov’t). In the end, as somebody rightly pointed out in this Twitter discussion, the market for any residential internet is folks who don’t have access to fibre x are willing/able to pay 100 USD per month.

My last case study would be Ground Segment as a Service (the thing other satellite operators use if they don’t build their own antennas to receive information from space/send instructions from the ground). On the fixed costs side it is to build, transport and install the antenna. Typical suppliers would be Safran or Orbit CS. Some build their own ground stations, but it gets complicated as you move towards higher data rate bands. On the operating costs you have rent, electricity and fiber on site. On the revenue side, it is a price per minute x occupancy rate (how much time of the day you have paying clients) x minutes per year = total revenue per station. That again gets a bit more complicated with some fixed reservation fees and premiums for priority access/last minute pass requests. But again, you can quite quickly model in like 60 seconds in excel what to approximately expect from GSaaS.

Part 2 - more context

Embarrassingly simple

I’m actually quite ashamed of the last case study. Early in my space career, I worked at a Ground segment startup, and for the whole 1.5 years or so I stuck in there, I thought that our business model is some extremely difficult math which I will never be able to comprehend. How awkward!. Feel free to take off some time to make fun of my inability to realize the business model I thought was super complex is actually elementary school algebra.

Much more transparent space

But perhaps to my defence, six years ago or so when I started, there was much less pricing information available about the space industry. Obviously, it is difficult for me to objectively judge, because 6 years ago I was a very different person and so maybe this is just my bias. Nevertheless, the SPACs wave in 2021 brought to the public eye a lot of nonsense, but also some useful data about M&A, costs and revenues of space startups. Secondly, some companies made a conscious effort to make their product pricing public (OrbitFab with their Refueling and Rafti prices, Apex Spacecraft with their spacecraft bus cost, SkyFi with their imagery prices). Transparent pricing always comes with a sacrifice of not being able to price-fix customers based on a perceived ability to pay up - but in the long run opens for customers who otherwise wouldn’t be willing to deal with all this nonsense.

Chocolate factory business model school

I think this will be increasingly a challenge to young people - business models get complicated. A hundred years ago, I’d interacted mostly with manufacturing/retail businesses, some basic services and transportation networks. Today, in contrast, most of the businesses I interact with are weird network/platform/financial plays - even Starbucks is actually a bank occasionally selling coffee. But any time I am explaining or thinking about some business concept, I always start from some elementary business model (input commodities, exit final products, buy low, sell high, add value in between) like a steel mill or a chocolate factory (given my obsession) instead of some subscription platform marketplace on blockchain.

If all analysis is simple - what is hard then?

Since I boast that space business is that simple and you can quickly assess any business model - why do people continue to pay expensive business advisors and space company business models are still suboptimal + how do you recognize a good business estimation for a bad one?

For a serious business analysis - you will need much better data than what I present. The reasons are twofold - in my proxies up in the article, you can easily hit or miss the target by 30, 50%. That is okay to get a ballpark estimate (typically if I want to quickly guess whether a business is VC-scalable or not), but of course if you run your own business and you underperform by 30% you will not be happy. More importantly - if you can do a quick business estimate, your customers can too. Some business analyst/procurement person from your customer can do the same math and find out you are massively over-charging them. Right now, that might be less the case as space business is still in its infancy, but if the space business really lifts off that will be less and less the case. So once you are making difficult decisions, you will need to collect more data, consider more details and perform the classical (long and more expensive) business analysis.

Knowing the data and where to search for it is one of the aspects of splitting apart good and bad quick proxy analysis - as is the ability to select-pick the most important model inputs/aspects for each business. Recently, somebody absolutely blew my mind off by suggesting they have absolutely no clue how long satellites stay in orbit (the most important number for any space business). Finally, understanding the quality of data, nuance and subtleties again splits apart good estimation and a bad one - you could think it is a great idea to pay 25k to launch 1 kg on the Electron rocket, but you are in tough luck since you will still have to pay the full $7.5M.

As I’m writing this now, I think the decisive skill in venture capital might not be business model analysis. I know my colleagues across the business are smart people who can do the same as I just showed. Instead, it might be about ability to think bigger/have an ambitious imagination, being able to get an access to companies early at a low price.

How to understand finance

I spend an absolutely ridiculous amount of my time explaining basic finance concepts to people. To startups, what are we looking for (10x), why are we looking for it (we promised X back to our LPs). Here is another useful proxy.

Anytime you see a VC investing X in a company, think they will want 10x back in 7 years. (It might be a bit less past Series B, the later you get the more the return expectations converge to PE-style)

So if a startup just raised 10M, their VCs will want 100M back in the next seven years, while accepting a high likelihood of failure. If that is not happening, you know that somebody is in trouble. VCs might try to reshuffle the management or maybe sell the company so they can return the proceeds to their investors or reinvest them.

For PE, a good proxy is 2x in 5 years. The failure rate is lower, the entry price is higher, between 2000-2021, PE has done some 11% per year - this is a good approximation.

When Advent International acquired Maxar, everybody was like - wow! What are they ever going to do with it. In the end, the answer is actually pretty simple - any business is a combination of revenues, costs and capital. Maxar works to increase the revenues (new satellites), decreasing the costs (firing people) and…

Needless to say, you can also quickly estimate startup burn. Assuming personnel is the biggest costs (the more hardware the less true, and questionable with compute prices), you get a low burn estimate of a US company by 150k year * number of people. With 450 people on VAST’s staff, assuming 350 of them Full time (no idea, just guessing), we are at a massive 52M per year in headcount costs only. Oh wow! Let’s hope Jeb McCaleb has a lot more crypto money to fund this.

How to do market sizing

I see so many ridiculous TAM slides in pitch decks, or better, I ignore them completely because they are usually complete nonsense. Three mistakes I see most commonly

Starting from the 400B space economy figure - since most of that number are PayTV subscriptions and GNSS receiver devices, it is largely completely irrelevant to new startups

Often I also see folks starting with the figure showing whatever 100k satellites in 2030 - was majority of which are/will be one or two or three megaconstellation and thus not impacting your TAM

I also have no idea where this SOM/SAM/TAM thing came from and who ever thought it would be a good idea. I frankly don’t know what the two S-things mean and never want to know. Secondly, it seems to me that is it just so far from daily business operations. Recently I saw some idiotic TAM estimation which combined the AI and Drone and Satellite markets into some 1 Trillion figure… wtf!?

The way to do it right - simpler = better.

Number of potential customers

x

how much do they averagely spend for this product/service in a year

I also like this proxy because it quickly helps to get an idea of how the sales organization will have to look like + the risk profile. As I wrote in one of my past essays on large terrestrial markets - I am very nervous about space companies relying on a single digit number of (however big) governmental contracts, simply because it doesn’t allow much room for error. In the mice/bee types of companies, you can test your sales process on the first 50 customers and then use it to optimize the process for the other 5000. If your total TAM consists of 10 customers, you better nail everyone of them.

If you feel like the above equation doesn’t do justice to your business model - you can add one or two more tiers - similarly to Starlink charging very different prices to residential and about 10-100x more to aero/maritime/defense customers.

Another question is how much do your customers want the service you are providing and how many competitors do they buy from - the least sticky business will probably be retail/fmcg where you make a new choice every time in a store - the most sticky would be multi-year leases etc.

The other part would be the difference between value creation and value capture - i.e. every month I spend around $300 for food, but that obviously doesn’t mean you should go build your next startup in food just because there is a multi-trillion USD TAM.

Lessons from Silicon Valley

Earlier this year I co-wrote and helped co-teach a class at Stanford and paired that with a great week learning from investors, entrepreneurs and big money people. I also attended an earlier lecture from the course I contributed to. And we discussed exactly the part above, we took several space startups/businesses the class recognizes, and relatively compared them using the how many # customers are there and how much are they willing to pay.

And this is again why I am so keen on space businesses which provide services to existing industries on Earth. The customer magnitude will always be really big, the ARPA usually mediocre but still leading a decent business. Contrasting that with businesses providing small satellite missions - you have some 500 smallsats per year max, many in problematic countries, and smallsats are not that expensive so people aren’t willing to pay much.

I use this to quickly assess startups, but equally to judge strategy shifts of existing businesses. For example - OrbitFab first advertised a 20M refueling price tag for 100 kg of mass to GEO, now they are selling Rafti refuelling port for 30k a piece (while continuing to work on the old business). Is it a good business mode? Let’s use the simple model above.

Refuelling costs 20M and has probably 100 potential customers per year - so 2B USD per year TAM. Rafti port costs 30k and Assuming Starlink doesn’t begin to buy them, that is 400 satellites per year, yielding a TAM of 12M. That revenue is obviously much more accessible with much less capital expenditure required, but it doesn’t sound like the type of win Orbit Fab needs to make 10x on their 28.5M round by 2030.

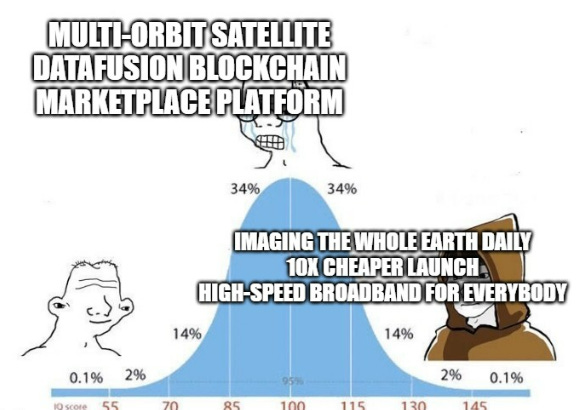

The other lesson I noticed in the US/Silicon Valley: everybody thinks in a much simpler way about business. I think it is a combination of two factors - to get through 150 pitches a week to raise your seed round, you probably really need to narrow down your message as much as possible. And secondly I’d just guess it is the natural American-style confidence: don’t limit yourself by self-imposed constraints.

But really, think about this:

Planet: imaging the whole Earth every day

SpaceX: 10x cheaper launch by reusability

Starlink: high-speed broadband for everybody

Astranis: 10x cheaper GEO satellites

Of course, it is a survivorship bias in part, but in Europe, I keep meeting startups like “payload interoperability marketplace using blockchain and NFT for additional monetization”

…excuse me what?

Thanks for reading. My personal email is me@myfullname.com; my VC email is myfirstname@expansion-vc.eu. Feel free to get in touch if you have thoughts/questions or want to pitch (a simple) business idea.

Love me some VC math