When Big Finance Enters the Space Industry

Why ice cream stand doesn't need an investment banker - but space startups do.

You won’t need investment bankers if you want to run an ice cream truck. You might need to use up your savings or a business loan, but it’s not likely you will go public via SPAC, reach revenues only 10 years after starting selling ice cream or be required to down pay 40% upfront to join a government-funded research programme to discover new ice cream flavours. If you, however, like to run a space company, all of these scenarios can occur and finance people will have a say in your business. Taking a glimpse into their world is thus a useful idea - let’s take a quick look around.

Housekeeping notes

Most of the smart things said in this article don’t come from my head, unfortunately.

Understanding the world of finance is much about the learning process & understanding the mindset than any specific facts. The purpose of this article is to pile a lot of facts together, but ultimately the aha moment occurs in the reader’s mind.

Often times I employ an approach of “reasonable guesses”. I, of course, can’t speak about the details of transactions I know. So instead, I take transactions where I don’t know confidential details and talk about what is the likely mechanics behind them. I have analysed hundreds of transactions recently, generally confirmed by insiders, so I’m fairly confident about my assessment.

Key takeaways

I didn’t get to summarize tonight. Either I add it here later or make a separate article/post tweet. If you are desperate for Tldr, send me a message - unlike my report, this summary is for free.

Table of contents

Opening

Housekeeping Notes

Financial people are different (establishing a difference in thinking of finance and space people)

Why finance exists (coming back to econ 101 and thinking about fundamentals)

The macro view (portfolio is the keyword)

Specific examples (taking a look at some 2021 transactions and applying the finance lenses to understand them)

A few implications (some random snippets on what how finance and space interact together)

A primer on roles (handbook-like section on financial roles relevant to the space company lifecycle)

Applying this article (a few tips you can actually incorporate into your business)

What else could we talk about (storage of ideas for my next article)

Learning resources (if you feel like your reading list is not long enough)

Finance people are different

A lot of my time is spent explaining relatively foundational finance to space people - how do public companies raise money, how are VCs compensated, what is this private equity thing all about? On the contrary, finance people don’t ask me about the difference between hyperspectral and thermal imagery, mostly because they don’t care. They have plenty of different questions to ask, tho.

Finance and space people are different. My last set of discussions with space startups revolved around the GSD of hyperspectral imagery, stationkeeping for HAPSes and parameters of solar cells. The topics of my conversations with finance people were - deployment strategy for Fund-of-Funds, finding a hedging tool against shorting [a particular group of public companies] and trade-offs of types of exposure to the space economy.

To demonstrate the contrast perhaps one more time - when one of my great mentors was introducing me to institutional finance, he made a very correct remark that finance people care basically only about three metrics when evaluating a company - revenues, costs and capital. That is, again, extremely different from how people in the industry evaluate their partners and competitors.

I get a lot of responses saying that finance people talking about space are thoroughly incompetent (which is often possible to agree with) and wishing for space to be solely led by technical personnel. If space is not going to be a small, government contracting endeavour, finance people in the space industry are here to stay - and again, let’s take a glimpse into their world.

Why finance exists

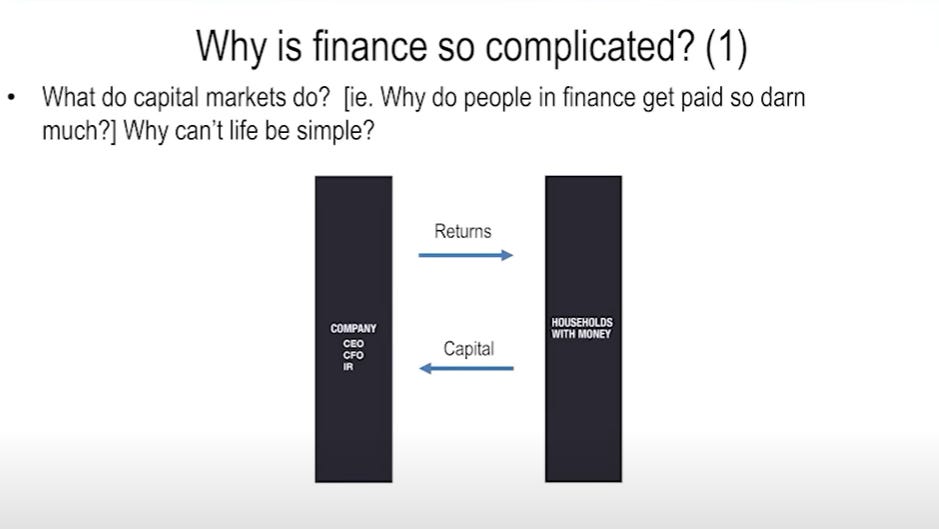

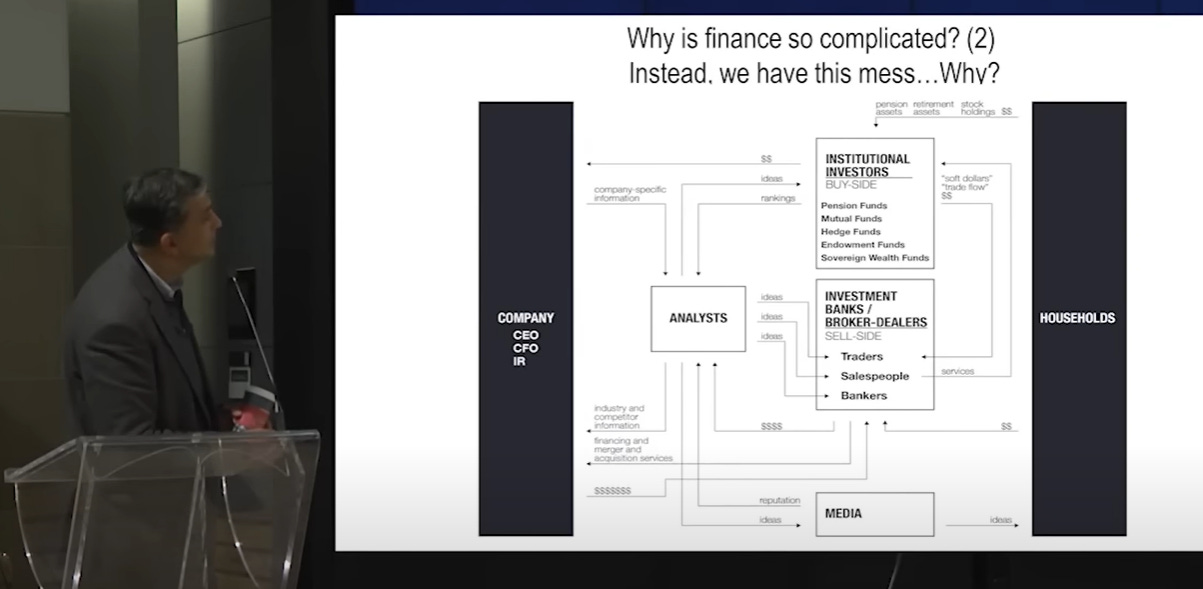

If you take any Economics 101 course, one of the first few lessons will discuss this genius diagram. In short, it says that households (that means you) have cash savings which they want to benefit from, while firms (the companies you work for) need capital to fund their operations. The whole massive finance industry - all of those people in suits in Manhattan, the City and Canary Wharf are here simply to facilitate the flow between those entities.

There are two topics I will dive in later in the article - finance as a problem-solving tool and cash flow management. But just to touch upon it now - In life, there is always a disparity between when you have money and when you need money, whether in personal finance (you earn money in a job now to be spent on retirement thirty years later) or in the industry (you need to build the factory now only to sell satellites in five years). And this is why the two major parts of finance - lending and investing developed.

One of the other economic concepts to take into account is specialization. My neighbour next door is a football coach - he makes more than he spends, but he doesn’t necessarily know how to invest his money - which is why there are professionals investing on his behalf (and plenty of others). Similarly, on the buy side, the roles are still split between people who decide on the overall portfolio allocation (“10% of our assets under management will go to early-stage venture capital”) and those who manage to invest in that specific asset class (the Fund-of-Funds which will select the specific VCs).

Aligning incentives, the flow of information and specialization is also a reason why finance appears so complicated. Consider those two slides from How Finance Works: The HBR Guide to Thinking Smart About the Numbers - Mihir Desai to be found here.

One of the coolest facts I know is that there is a literary asset class betting on movies. When Fast and Furious has been in the making, likely some investors backed the movie - filmmakers tend to not walk around with 40M in cash. They probably got paid handsomely back. Finance is a literary part of almost every aspect of our lives.

The Macro view + Capital Allocation

Earlier this year I took a trip to New York to meet with finance people. One of the confusing things to me is the confidence with which they say - “space is gonna be big”. Being in the industry every day, I see GEO operators struggling to compete with LEO providers, LEO operators struggling with unit economics and supply chain, and companies failing, consolidating and being destined to fail (launchers, propulsion) since the beginning. Even companies with strong customer bases and leadership teams can get into significant trouble for seemingly minor issues with reaction wheels or acts of God events like magnetic storms.

The other confusing thing big finance people like to say is that space is still too small for meaningful investment. ?!?! Every day, some industry colleagues come asking for investment or to complain about how difficult it is to raise money in this environment. And then institutional investors will say the space industry is still too small to invest in.

Regardless of the size, every investor needs to gain funds somewhere and make an offer to the holders of capital. “I will do my best to achieve this return, this potential upside at such and such level of risk." I will do it in this geography and this asset class.” The key word here is obviously diversification. Further in the article I take a closer look at VC expected returns, but every time you want to understand a finance transaction in the space industry, try to consider what was the specific mandate of that given investment vehicle.

Specific examples

I will rush through this section because I delayed the publication of this article for too long. I will always introduce a bit of the context to the transaction and then try to comment on it from the big finance perspective.

In October 2021, Loft Orbital raised a $140M series B round led by BlackRock. It was also probably the last major round in the sector before markets hit a downturn 5 months after.

First, Loft is a business for investors to like - infrastructure business model, an experienced management team with traction in the business world, proven technology (using OneWeb buses) and existing customer base with a good gov’t/commercial mix. Broadly there is a consensus that all good businesses share some major traits regardless it is a satellite operator, steel mill or chocolate factory.

While BlackRock has done some space deals, there is no team with a space specialization (to the best of my knowledge). The truth is that BlackRock is one of the largest asset managers in the world - thus they have to have a private allocation from both return/risk and capacity to deploy (how much cash can but put to work in a given market) considerations. Notably, taking the most likely wrong Crunchbase data as a proxy, BlackRock exited about 1/3 of their private market investments. BlackRock indeed invests in businesses which can go public within 1-3 years which is a good trade-off for the availability of relatively large checks, notable derisking and still also a notable markup when going public.

Tldr - regardless how impressed the BlackRock team might have been with space, the idea here is that Loft is close to having a reasonable outlook of going public, which is where the BlackRock private allocations team often invests.

Also in 2021, Relativity Space raised 650M at a 4.2B$ valuation. Now, it is a bit difficult to imagine investors being too excited to fuel 650M in a company which previously raised about the same amount and launched exactly zero rockets at the time (and abandoned their flagship model right after the test in 2023).

Again, I suppose it has to do with the fact that some of those investors (Fidelity, Tiger), indexed basically every late-stage technology deal, as that was the only place really where their amount of capital was able to be put into work. Secondly, Relativity went on a wave of at the time super popular 3D printing. Investors love to take random words and make them guide their asset allocation decisions.

Now, I’d like to talk a bit about a section from Ian’s SpaceDotBiz newsletter. It basically talks about the same idea I tried to convey above - the capacity to deploy. To reiterate, some institutional investors still cannot invest in the space industry because the rounds are not big enough. That is a problem because (1) the due diligence and transaction costs are too high compared to the total investment size (2) the absolute dollar return is not meaningful (3) the investment size is not relevant compared to the total amount of capital under management of those institutions. That applies both to institutional investors who were traditionally interested in the A&D sector, as well as those actual strategic players.

Let’s stick with launchers (the reason I speak this much about launchers in this section is that they are by now a big enough category for me to be meaningfully talking about the underlying financial decisions, rather than the lead VC and startup person doing their undergrad together). I also write here mostly about 2021 transactions - I had a chance to watch them for a while, and understand the companies’ progress after a raise and that hopefully gives me a bit more clarity on how to analyze them).

In the summer of 2021, Gilmour Aerospace raised close to 50M USD series C. The press release reads: “The Series C round, which includes US-based Fine Structure Ventures, Australian venture capital firms Blackbird and Main Sequence, and Australian superannuation funds HESTA, Hostplus, and NGS Super” (emphasis mine). Now the question is, how do random three pension funds get on board a launch company? I can’t say for certain, obviously. But one of the very common reasons for larger investors to become LPs in early-stage VCs is not really about the financial returns, but rather their scouting ability and relationship building, so those investment funds can join later rounds of their VCs’ most promising portfolio companies directly. So this is my theory about how three pension funds got on board a launch company. Australia is a very interesting market with an incredible amount of pension pool money - but that would be for another article.

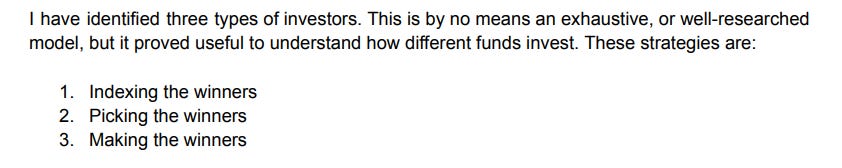

Alumni Ventures is one of the very common investors in the space industry. That is interesting - you don’t see Alumni people writing articles about the future of space, they are (to the best of my knowledge) not wandering about satellite shows they don’t write books about the future of business in space. The point, is they have done about 1500 investments in total, 50 already this year. In my 2022 report, I have talked about a proxy for three types of investors - Alumni is clearly the indexing type. And they are doing it rather well.

In contrast, A16Z has been very very reluctant to invest in space (a market map ain’t gonna change that). But they love to make winners - think how much cash they have already sent to Astranis.

(I wrote this before they split into three firms. I don’t know anything about the splits of VC firms. What I wrote still holds true I believe). Out of all of the major US VC firms, Sequoia is still the last one who is yet to invest in a real US space company (they have invested in a late-stage SpaceX deal, Vector Launch and apparently also Rosotics). On the other hand, Sequoia Capital China is one of the prominent commercial investors in the Chinese space industry. When bit asset allocators make their allocation - they are considering risk, return and also a number of diversification strategies including by geography. So the fact that out of the former whole Sequoia firm, only the US arm has done major space deals should be very much aligned with how their LPs think about geographic diversification.

related story - I met a filthy rich lawyer (who is actually an LP in one space fund) who told me: all of my wealth and income comes from [a European country]. In contrast, when I think about my investment portfolio distribution, I have projects and private funds in almost every major country around the world. So if something goes bad here, I still have an alternative.

A few implications

Space Venture Capital is a minor part of the global institutional money allocation. I present you two breakdowns - for pension funds which are more conservative and family offices. Broadly, the major portfolio allocation always goes to stocks and bonds. All alternative assets are constituting a minor share of the portfolio. Private Equity is only a fraction of the alternative assets allocation - further splitting into mature companies/buyouts, growth and venture capital. And then, within all possible areas to invest in, there is indeed also space tech. While those graphs aren’t a full representation, they serve as a good proxy to understand what are the institutional allocations like.

Going public is really a way to unlock access to a much larger pool of capital. Even here, things still can get more tricky. It goes without saying those companies must be ready for a life as a public company. The other problem is often a lack of analyst coverage (see “A primer on roles”). Some institutional investors have the mandate to invest only in stocks which have some degree of coverage by analysts - who are compensated by the trade volume. So going public is not the definitive treat, those companies must attract sufficient trade volumes and ideally also become a part of major tracked indexes.

Overallocation to venture - why LPs are exiting their VC positions. Institutional investors have defined some form of strategy and resulting preferred breakdown by asset classes. One of the issues which occurred after the 2022 downturn is that valuations in private markets stayed surprisingly high relative to the publicly traded parts of portfolios. Thus, actually, many institutional investors have to exit some of the private market positions as a part of the rebalancing, not because they wouldn’t be performing well, but in spite of the opposite. This unfortunately again doesn’t come from my mind - I have to credit Adeo Ressi, the head of VC Lab who said it at one of their webinars.

There is a cornerstone corporate finance book called Valuation by Tim Koller et al. The book basically says that value creation depends on growth and the Return On Invested Capital (ROIC). When a company grows while maintaining an ROIC higher than the cost of capital, a positive value for shareholders is created. Now, let’s think about two facts (1) the cost of capital radically increased in the last two years (2) and different divisions within corporations have distinct ROICs. The assumption is that the divisions with lower ROICs would be better suited in different companies, where they could better justify their standing. Spinning out corporate divisions between companies was really popular in the past 12 months and this is the reason.

How you can buy a company without money. This is a point I did not properly emphasize in my PE article. It is mind-boggling. Imagine you want to buy a chocolate factory which makes 10M a year valued at 100M. You go to the bank, you borrow against the future revenues of the company. You buy the company, make it naturally grow 10% a year, pay the 5% interest from the growing revenues and in 10 years, you have no debt but the whole factory. You have just bought a chocolate factory for free. Welcome to the world of private equity.

When 1$ isn’t always worth 1USD. This was also first confusing to me. Imagine a vacuum chamber costs 10 USD. Now, apparently, its price can be only 2 USD if Virgin Orbit owned it previously. I won’t dive into the world of bankruptcy law today, but in the finance world, there are all sorts of discounts and premiums which are good to be aware of. Maybe the vacuum chamber would be $12 if it merged with another vacuum chamber - they might cost less to advertise afterwards.

A primer on roles in finance interfacing the space industry

In this standalone section of the article, I would like to briefly explain the major roles /types of players you can meet when at the intersection of space and finance

Investment bankers

The most confusing fact to digest is that investment bankers don’t really invest. They mostly work around two topics - M&A and capital raising.

M&A teams work both on behalf of both the acquiring company and the target to establish a fair valuation of the company, conduct due diligence, and assemble the acquisition together (including the different financing scenarios including a combination of cash and stock, debt financing and different types of payouts) and help align all parties and interest in the process.

How it might work is that a company has an informal discussion about its future. Afterwards, acquiring company A submits an official offer to acquire company B. The board of Company B has a duty to seek the best offer - thus, an M&A team will create a list and contact possible buyers on behalf of Company B to establish a competitive bidding process. Afterwards, the best offer is exercised. My favourite example of trying to establish a bidding process is OrbComm not getting any offers “after contracting more than 50 potential buyers.

Capital raising teams help connect companies looking for funding - both in the form of investments, strategic investments and debt financing with investors looking to put cash in the works. Until the raise size exceeds, let’s say, $20M, it is probably not worth engaging with investment bankers. But from that size onwards, companies begin to look for more institutional investors not easy to find or well-versed in that specific market sector. Investment bankers help those investors find deals and thus have a network of investors with which they can share deals. A good example of capital raise where investment bankers engaged was Liberty Capital investing in Satellogic.

One more informal but useful distinction to add is by size. With a lot of generalisation, we can say there are small boutique investment banking shops (like Quilty Analytics) and then the usual suspects of big banks like Barclays or Goldman Sachs. My rule of thumb is that boutique shops know the industry much better and are best suited for strategic deals or sub-100 M deals.

Sell-side analysts

Sell-side analysts may actually sit in the same building as the investment bankers above. But otherwise, there must be a sealed wall between those divisions. Sell-side analysts provide coverage on traded security - or said otherwise, they analyse financial results and current news related to several stock titles on their cover and summarize those into research notes, which buy-side investors can use when constructing their portfolios. Sell-side analysts get a cut of the trade volume of the stock titles they cover. Morgan Stanley’s notorious example is part of its wider coverage. DB downgrading Astra could be a bit better example.

Corporate Development

Corporate development has a much wider mandate than M&A - but let’s put that on hold, and for now we can think of corporate development as dedicated M&A teams inside corporations. It is in their job description to be on the lookout for interesting acquisitions. Although sometimes, they might be just the executive team for conduct of transactions selected/suggested/recommended by other company departments such as R&D, software development or supply chain. For example, Planet has effectively created its corporate development team just before going public and has been acquiring about one company a year since.

Applying this article

You can’t get your dessert before dinner, but after this much introduction, it is perhaps time to explore how this article can be applied. I’m largely inspired by two European startups - one came to me asking, we saw the Exploration Company raising 40M, why can’t we get the same deal? With the other company, we discussed exit options. It was clear they won’t go public. I told them some vertically integrated holding would be an option - the response was “We don’t really know how this works”.

Finance as a tool for solving problems

First, I’d like to work with a paradigm that finance is really a way of solving problems. Think of a couple of examples.

Fundraising is the most elementary - a company needs cash injection to gain market share, which will help to offset initial development costs and together with efficiencies of scale will make the company profitable. So they go out and raise this risk money in exchange for equity in the company.

Founders payout - “We have been building this company for six years now. I feel strongly motivated to continue but would like to partially cash out so I can do some long-delayed house renovation” While this is unthinkable at the seed/pre-seed stages, it is actually perfectly possible that at a later round, the VCs will invest directly into the company, but also buy some shares directly from founders. This allows VCs to get a higher share than what the company has allocated and provides partial liquidity to founders.

Secondaries - early investors in companies are usually bound by their fund horizons to exit in 5-10 years after the investment. It is possible the company has an interesting paper valuation but no IPO/acquisition in sight. This is where secondary funds might step in - to buy shares on a so-called secondary market (not via the primary issuance) at a discount to the current valuation. For the secondary buyer, this offers an attractive buy at much lower risks - for the early investor, this allows for a much-needed hard cash return which can be distributed to LPs.

Chris Wade from Isomer Capital said that this is how GPs become adults (general partners - those who run VC firms) - when they take capital from LPs, invest it, make a markup and return appreciated capital back to the original investors (as opposed to just rolling with yet to be realized gains).

SpaceX is one company I know of where secondaries are sold at a markup rather than a discount simply because it is difficult to get in.

Bridge rounds - I started seeing this in the space industry in 2020/2021. Often companies plan a major raise with certain financials and milestones which justifies a valuation. As goals might often take longer than anticipated, bridge rounds come into play to provide a temporary runway before the major raise at a discount to the next round to justify the risk. Before ICEYE raised a massive $136M series D in early 2022, Seraphim helped with $25M in December 2021.

Vested shares - this is a great invention. I’m by very very far not a lawyer, so do not quote me on this. But in the US, it is a convention founder shares are vested over a four-year period. In that way, if one of the founders with a major share decides to leave the company in a few years after founding, for whatever reason - the company isn’t left as an uninvestable firm with 30% deadweight equity

Okay. That was indeed a bunch of examples - so my first attempt for a recommendation - a lot of your problems are quite likely to have a finance-supported solution. Look for them.

This is also the reason why my report is so favourably biased towards finance.

Understanding the types of returns

The type of investor you bring onward determines the type of returns they look for. I don’t know a lot about what strategic investors or institutional lenders look for (the answer will be, of course, it depends). But I know a bit about the types of returns VCs look for.

Let’s say you have a 10M VC fund

You need to at least beat the inflation - at 3% a year, you need to return 13.5M to not literary lose money.

You should at least beat the stock market, assuming an 8% a year return, we are looking at 21.6M over a ten-year period.

Now assume you can invest only 8M of that 10M because the rest will be consumed by a 2% per year management fee. So you still need to return the 21.6M, but now only from 8M, you will actually invest.

20% of any returns will be delivered as a carry fee to the management of the fund - thus you need to return 20% more overall.

Given a 90% failure rate, this whole payout needs to be from one company. Let’s say you get diluted 2x by 20%. By extremely rough and generalist calculations, the company needs to exit at about 400M to make the VC investment comparable with the stock market.

There have been plenty of better articles written about this. The message is to understand what type of returns VCs look for and to seek an understanding of what type of returns other investors look for. The 10% a year S&P500 is a useful benchmark to think about - “will my investor do better investing in the stock market or into my company?” (and yes, there are tax advantages, intangibles and impact-type of benefits; yet this serves as a simple math).

Interestingly, this dynamic changes with a big enough fund. If your portfolio is, let’s say, 1000 reasonable startups, there is a decent chance you catch let’s say 5-10 unicorns. So extremely wide indexing approach allows to a decrease the transactional costs, and increases the chance of success. In this case, the mandate is not to pick a winner but to index the market for those who can afford it.

Tldr. If you invest 1M today and get 1M back in 7 years, you are not even - you have made a terrible loss.

Cashflow

Cashflow management is an area with I see as (1) an immediate concern for a lot of companies around and (2) belongs to a category of solvable problems. Most typically, companies should at least try to ask for a down/milestone-based payment when pursuing a contract. I don’t want to go much deeper into this, but to have a look at your cash flow is (tho very simplistic) tangible action you can take. The basic ones are hiring consultants and thus delaying full-time employees and negotiating for some amount of downpayment on every contract.

Developing the right relationships

Larger organizations and more sophisticated organizations take years to put a deal together. In the general tech industry, likely acquisition partners are those you have worked on projects together for a while and have a working relationship. So, attempt for a recommendation - when this is of interest, the relationship should be at a point where you can informally discuss the future of your companies.

There are plenty of people whose everyday job is to follow the market around your startup already. Your VCs are great people to start this conversation with - how big finance affects your space startup. The truth is, later in the process, C-level people in growth startups become extremely proficient and very good at this. For specific topics or outsourcable work - consultants are great. But please, for the love of God don’t let them reach out to investors on your behalf - those people will end up in hell. From my experience, investment bankers are really busy but will take a while of their day to share what could they do for you once you reach the relevant size.

Interchangeability of debt, revenue and equity

I don’t want to sound too esoteric so will keep this shallow. Debt, revenue and equity will in the end all translate as cash on hand in the company treasury and are bound to obligations (revenue - to provide a service; debt - to pay back + interest; equity - to deliver return on enterprise value, dividends). The right CFO is able to recognize which source of cash is suitable for which purpose. Funding announcements sometimes offer a glimpse into how other companies are solving this. Think of this deal between EOI and NTT Data.

What else could we talk about?

Why is understanding finance so complicated? Social Media/Platform Economy/Space messed up my basic intuition of finance. Now, when I’m learning the basics, I always try to imagine a steel mill or a chocolate factory. Here, the debt financing, ROIC, DCF valuation makes much more sense.

Debt financing, the second arrival of venture debt, non-dilutive financing and its implications - all super important topics

How to look at finance companies via the “product” they are offering

Institutional investment landscape - looking to understand HNI, Family offices, endowments, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and so on.

Why staying private longer is detrimental to society - companies tend to stay longer private these days than they have done historically. Pension funds and retail investors have thus a lower chance to benefit from this growth, which will lead to massive issues down the line.

Indexing/exposure. The stock market had become basically a tech index. Investors looking for exposure to the real economy must approach private markets via sectors like agriculture.

How the big people invest - Mubadala, Norwegian Sovereign Wealth Fund…. and why the latter doesn’t invest in private markets (probably a mix of governance requirements and the fact by the virtue of their spending any potential profits would be offset by the higher demand, a risk occurring when the price taker becomes a price setter)

What does “small cap PE mean” and is there an overallocation to venture?

Why shouldn’t GEO operators innovate? The business problems are already reflected in the cost of capital and the share price. Now they should only distribute as much cash as possible and wait to slowly die.

Learning resources

Finance: Masters of Business from Barry Ritholz on Bloomberg Radio; How Finance Works; Salt conference recordings

Venture Capital: Secrets of Sand Hill Road; Venture Deals

Private Equity: The Dealmaker (Guy Hands)

Corporate Finance: Valuation (McKinsey & Tim Koller)

Distressed Assets: The Art of Distressed M&A

A bit of math: Jake Xia’s Portfolio Management

If you have finished here - I’m very sorry for you. And also very grateful. Feel free to share your thought at me@filipkocian.com or kocian@golemventures.com. As a bonus, treat yourself to the best 81 seconds Hollywood has ever created.